Clang - Features and Goals

This page describes the features and goals of Clang in more detail and gives a more broad explanation about what we mean. These features are:

End-User Features:

Utility and Applications:

Internal Design and Implementation:

- A real-world, production quality compiler

- A simple and hackable code base

- A single unified parser for C, Objective C, C++, and Objective C++

- Conformance with C/C++/ObjC and their variants

End-User Features

Fast compiles and Low Memory Use

A major focus of our work on clang is to make it fast, light and scalable. The library-based architecture of clang makes it straight-forward to time and profile the cost of each layer of the stack, and the driver has a number of options for performance analysis.

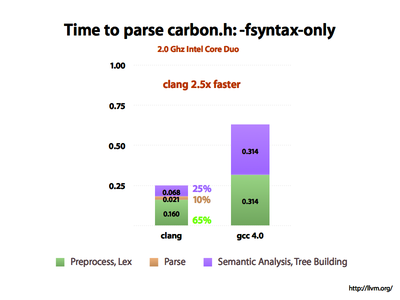

While there is still much that can be done, we find that the clang front-end is significantly quicker than gcc and uses less memory For example, when compiling "Carbon.h" on Mac OS/X, we see that clang is 2.5x faster than GCC:

Carbon.h is a monster: it transitively includes 558 files, 12.3M of code, declares 10000 functions, has 2000 struct definitions, 8000 fields, 20000 enum constants, etc (see slide 25+ of the clang talk for more information). It is also #include'd into almost every C file in a GUI app on the Mac, so its compile time is very important.

From the slide above, you can see that we can measure the time to preprocess the file independently from the time to parse it, and independently from the time to build the ASTs for the code. GCC doesn't provide a way to measure the parser without AST building (it only provides -fsyntax-only). In our measurements, we find that clang's preprocessor is consistently 40% faster than GCCs, and the parser + AST builder is ~4x faster than GCC's. If you have sources that do not depend as heavily on the preprocessor (or if you use Precompiled Headers) you may see a much bigger speedup from clang.

Compile time performance is important, but when using clang as an API, often memory use is even moreso: the less memory the code takes the more code you can fit into memory at a time (useful for whole program analysis tools, for example).

Here we see a huge advantage of clang: its ASTs take 5x less memory than GCC's syntax trees, despite the fact that clang's ASTs capture far more source-level information than GCC's trees do. This feat is accomplished through the use of carefully designed APIs and efficient representations.

In addition to being efficient when pitted head-to-head against GCC in batch mode, clang is built with a library based architecture that makes it relatively easy to adapt it and build new tools with it. This means that it is often possible to apply out-of-the-box thinking and novel techniques to improve compilation in various ways.

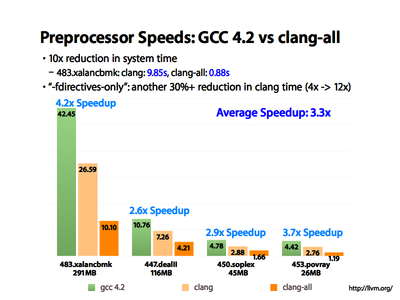

This slide shows how the clang preprocessor can be used to make "distcc" parallelization 3x more scalable than when using the GCC preprocessor. "distcc" quickly bottlenecks on the preprocessor running on the central driver machine, so a fast preprocessor is very useful. Comparing the first two bars of each group shows how a ~40% faster preprocessor can reduce preprocessing time of these large C++ apps by about 40% (shocking!).

The third bar on the slide is the interesting part: it shows how trivial caching of file system accesses across invocations of the preprocessor allows clang to reduce time spent in the kernel by 10x, making distcc over 3x more scalable. This is obviously just one simple hack, doing more interesting things (like caching tokens across preprocessed files) would yield another substantial speedup.

The clean framework-based design of clang means that many things are possible that would be very difficult in other systems, for example incremental compilation, multithreading, intelligent caching, etc. We are only starting to tap the full potential of the clang design.

Expressive Diagnostics

In addition to being fast and functional, we aim to make Clang extremely user friendly. As far as a command-line compiler goes, this basically boils down to making the diagnostics (error and warning messages) generated by the compiler be as useful as possible. There are several ways that we do this, but the most important are pinpointing exactly what is wrong in the program, highlighting related information so that it is easy to understand at a glance, and making the wording as clear as possible.

Here is one simple example that illustrates the difference between a typical GCC and Clang diagnostic:

$ gcc-4.2 -fsyntax-only t.c

t.c:7: error: invalid operands to binary + (have 'int' and 'struct A')

$ clang -fsyntax-only t.c

t.c:7:39: error: invalid operands to binary expression ('int' and 'struct A')

return y + func(y ? ((SomeA.X + 40) + SomeA) / 42 + SomeA.X : SomeA.X);

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ^ ~~~~~

Here you can see that you don't even need to see the original source code to understand what is wrong based on the Clang error: Because clang prints a caret, you know exactly which plus it is complaining about. The range information highlights the left and right side of the plus which makes it immediately obvious what the compiler is talking about, which is very useful for cases involving precedence issues and many other situations.

Clang diagnostics are very polished and have many features. For more information and examples, please see the Expressive Diagnostics page.

GCC Compatibility

GCC is currently the defacto-standard open source compiler today, and it routinely compiles a huge volume of code. GCC supports a huge number of extensions and features (many of which are undocumented) and a lot of code and header files depend on these features in order to build.

While it would be nice to be able to ignore these extensions and focus on implementing the language standards to the letter, pragmatics force us to support the GCC extensions that see the most use. Many users just want their code to compile, they don't care to argue about whether it is pedantically C99 or not.

As mentioned above, all extensions are explicitly recognized as such and marked with extension diagnostics, which can be mapped to warnings, errors, or just ignored.

Utility and Applications

Library Based Architecture

A major design concept for clang is its use of a library-based architecture. In this design, various parts of the front-end can be cleanly divided into separate libraries which can then be mixed up for different needs and uses. In addition, the library-based approach encourages good interfaces and makes it easier for new developers to get involved (because they only need to understand small pieces of the big picture).

"The world needs better compiler tools, tools which are built as libraries. This design point allows reuse of the tools in new and novel ways. However, building the tools as libraries isn't enough: they must have clean APIs, be as decoupled from each other as possible, and be easy to modify/extend. This requires clean layering, decent design, and keeping the libraries independent of any specific client."

Currently, clang is divided into the following libraries and tool:

- libsupport - Basic support library, from LLVM.

- libsystem - System abstraction library, from LLVM.

- libbasic - Diagnostics, SourceLocations, SourceBuffer abstraction, file system caching for input source files.

- libast - Provides classes to represent the C AST, the C type system, builtin functions, and various helpers for analyzing and manipulating the AST (visitors, pretty printers, etc).

- liblex - Lexing and preprocessing, identifier hash table, pragma handling, tokens, and macro expansion.

- libparse - Parsing. This library invokes coarse-grained 'Actions' provided by the client (e.g. libsema builds ASTs) but knows nothing about ASTs or other client-specific data structures.

- libsema - Semantic Analysis. This provides a set of parser actions to build a standardized AST for programs.

- libcodegen - Lower the AST to LLVM IR for optimization & code generation.

- librewrite - Editing of text buffers (important for code rewriting transformation, like refactoring).

- libanalysis - Static analysis support.

- clang - A driver program, client of the libraries at various levels.

As an example of the power of this library based design.... If you wanted to build a preprocessor, you would take the Basic and Lexer libraries. If you want an indexer, you would take the previous two and add the Parser library and some actions for indexing. If you want a refactoring, static analysis, or source-to-source compiler tool, you would then add the AST building and semantic analyzer libraries.

For more information about the low-level implementation details of the various clang libraries, please see the clang Internals Manual.

Support Diverse Clients

Clang is designed and built with many grand plans for how we can use it. The driving force is the fact that we use C and C++ daily, and have to suffer due to a lack of good tools available for it. We believe that the C and C++ tools ecosystem has been significantly limited by how difficult it is to parse and represent the source code for these languages, and we aim to rectify this problem in clang.

The problem with this goal is that different clients have very different requirements. Consider code generation, for example: a simple front-end that parses for code generation must analyze the code for validity and emit code in some intermediate form to pass off to a optimizer or backend. Because validity analysis and code generation can largely be done on the fly, there is not hard requirement that the front-end actually build up a full AST for all the expressions and statements in the code. TCC and GCC are examples of compilers that either build no real AST (in the former case) or build a stripped down and simplified AST (in the later case) because they focus primarily on codegen.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, some clients (like refactoring) want highly detailed information about the original source code and want a complete AST to describe it with. Refactoring wants to have information about macro expansions, the location of every paren expression '(((x)))' vs 'x', full position information, and much more. Further, refactoring wants to look across the whole program to ensure that it is making transformations that are safe. Making this efficient and getting this right requires a significant amount of engineering and algorithmic work that simply are unnecessary for a simple static compiler.

The beauty of the clang approach is that it does not restrict how you use it. In particular, it is possible to use the clang preprocessor and parser to build an extremely quick and light-weight on-the-fly code generator (similar to TCC) that does not build an AST at all. As an intermediate step, clang supports using the current AST generation and semantic analysis code and having a code generation client free the AST for each function after code generation. Finally, clang provides support for building and retaining fully-fledged ASTs, and even supports writing them out to disk.

Designing the libraries with clean and simple APIs allows these high-level policy decisions to be determined in the client, instead of forcing "one true way" in the implementation of any of these libraries. Getting this right is hard, and we don't always get it right the first time, but we fix any problems when we realize we made a mistake.

Integration with IDEs

We believe that Integrated Development Environments (IDE's) are a great way to pull together various pieces of the development puzzle, and aim to make clang work well in such an environment. The chief advantage of an IDE is that they typically have visibility across your entire project and are long-lived processes, whereas stand-alone compiler tools are typically invoked on each individual file in the project, and thus have limited scope.

There are many implications of this difference, but a significant one has to do with efficiency and caching: sharing an address space across different files in a project, means that you can use intelligent caching and other techniques to dramatically reduce analysis/compilation time.

A further difference between IDEs and batch compiler is that they often impose very different requirements on the front-end: they depend on high performance in order to provide a "snappy" experience, and thus really want techniques like "incremental compilation", "fuzzy parsing", etc. Finally, IDEs often have very different requirements than code generation, often requiring information that a codegen-only frontend can throw away. Clang is specifically designed and built to capture this information.

Use the LLVM 'BSD' License

We actively indend for clang (and a LLVM as a whole) to be used for commercial projects, and the BSD license is the simplest way to allow this. We feel that the license encourages contributors to pick up the source and work with it, and believe that those individuals and organizations will contribute back their work if they do not want to have to maintain a fork forever (which is time consuming and expensive when merges are involved). Further, nobody makes money on compilers these days, but many people need them to get bigger goals accomplished: it makes sense for everyone to work together.

For more information about the LLVM/clang license, please see the LLVM License Description for more information.

Internal Design and Implementation

A real-world, production quality compiler

Clang is designed and built by experienced compiler developers who are increasingly frustrated with the problems that existing open source compilers have. Clang is carefully and thoughtfully designed and built to provide the foundation of a whole new generation of C/C++/Objective C development tools, and we intend for it to be production quality.

Being a production quality compiler means many things: it means being high performance, being solid and (relatively) bug free, and it means eventually being used and depended on by a broad range of people. While we are still in the early development stages, we strongly believe that this will become a reality.

A simple and hackable code base

Our goal is to make it possible for anyone with a basic understanding of compilers and working knowledge of the C/C++/ObjC languages to understand and extend the clang source base. A large part of this falls out of our decision to make the AST mirror the languages as closely as possible: you have your friendly if statement, for statement, parenthesis expression, structs, unions, etc, all represented in a simple and explicit way.

In addition to a simple design, we work to make the source base approachable by commenting it well, including citations of the language standards where appropriate, and designing the code for simplicity. Beyond that, clang offers a set of AST dumpers, printers, and visualizers that make it easy to put code in and see how it is represented.

A single unified parser for C, Objective C, C++, and Objective C++

Clang is the "C Language Family Front-end", which means we intend to support the most popular members of the C family. We are convinced that the right parsing technology for this class of languages is a hand-built recursive-descent parser. Because it is plain C++ code, recursive descent makes it very easy for new developers to understand the code, it easily supports ad-hoc rules and other strange hacks required by C/C++, and makes it straight-forward to implement excellent diagnostics and error recovery.

We believe that implementing C/C++/ObjC in a single unified parser makes the end result easier to maintain and evolve than maintaining a separate C and C++ parser which must be bugfixed and maintained independently of each other.

Conformance with C/C++/ObjC and their variants

When you start work on implementing a language, you find out that there is a huge gap between how the language works and how most people understand it to work. This gap is the difference between a normal programmer and a (scary? super-natural?) "language lawyer", who knows the ins and outs of the language and can grok standardese with ease.

In practice, being conformant with the languages means that we aim to support the full language, including the dark and dusty corners (like trigraphs, preprocessor arcana, C99 VLAs, etc). Where we support extensions above and beyond what the standard officially allows, we make an effort to explicitly call this out in the code and emit warnings about it (which are disabled by default, but can optionally be mapped to either warnings or errors), allowing you to use clang in "strict" mode if you desire.

We also intend to support "dialects" of these languages, such as C89, K&R C, C++'03, Objective-C 2, etc.