This HOWTO documents the View class, part of the Woven framework. The Woven framework should not be used for new projects. The newer Nevow framework, available as part of the Quotient project, is a simpler framework with consistent semantics and better testing and is strongly recommended over Woven.

The Woven documentation below is maintained only for users with an existing Woven codebase.

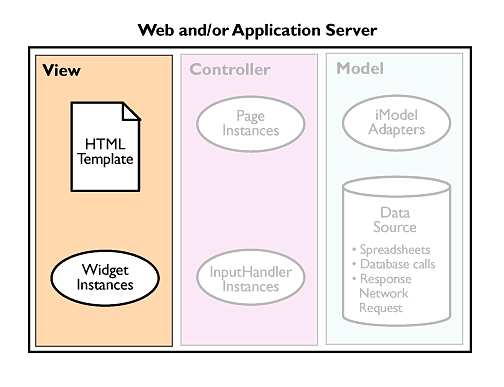

View objects are given a Model and a template DOM node, and use the DOM api to insert the given Model data into the DOM. Views are where you manipulate the HTML, in the form of DOM, which will be sent to the web browser.

'view=' directive to an instance of a View class.View factories provide the glue between a view= directive on a

DOM node and a View instance. When a DOM node with a view=

directive is encountered, Woven looks for a corresponding

wvfactory_ method on your Page instance. A View factory is required

to return an object which implements the interface IView:

class MyView(view.View):

def generate(self, request, node):

return request.d.createTextNode("Hello, world!")

class MyPage(page.Page):

def wvfactory_foo(self, request, node, model):

return MyView(model)

A View factory should almost always construct the View with the Model object it is passed. The exception to this rule is when the View is designed to render data which is not available in the Model tree, such as data which is obtained from the request or from a session object:

class MyPage(page.Page):

def wvfactory_currentPageName(self, request, node, model):

return widgets.Text(request.prepath[-1])

Note that if the Model the View is constructed with is not the Model which was passed in to the factory, Woven will notice this and place the new Model data on the Model stack.

You may set View factories programatically on a generic Page instance after it has been constructed. The first View factory example could be written:

class MyView(view.View):

def generate(self, request, node):

return request.d.createTextNode("Hello, world!")

resource = page.Page()

resource.setSubviewFactory("foo", MyView)

The generate method is the most important method in the IView interface. It is the entry point from the Woven framework into your custom Python View code. When your View instance was constructed, it was passed a Model as the first argument. This is the Model data which generate should insert into the DOM. generate is passed the request and a template DOM node, and must return a DOM node, which will replace the template in the DOM tree:

class MyView(view.View):

def generate(self, request, node):

return request.d.createTextNode("Hello, world!")

Note that the current DOM Document object is available as request.d. You should use this document object as a text node and element factory, so the details about the underlying DOM implementation remain hidden.

Often, it is incredibly useful to use the incoming template node as a skin

for your Views. In the simplest form, this involves simply adding nodes to the incoming template node and returning it from generate:

class MySkinnedView(view.View):

def generate(self, request, node):

modelData = self.getData()

newNode = request.d.createTextNode(str(modelData))

node.appendChild(newNode)

return node

However, Woven also supports the concept of pattern=

nodes, nodes which are marked in the template with a given pattern=

directive so they may be located by the View abstractly. To support this, Woven contains a View subclass called Widget, which provides a far more convenient API for rendering your Views.

Rendering Views is such an important part of developing a Woven application that it needs to be as convenient as possible. To support reducing the amount of boilerplate required to write a new View, the View subclass Widget was created. When subclassing Widget, simply override setUp instead of generate. setUp differs from generate in that it is passed a reference to the Model data, not the Model wrapper, and may simply mutate the template DOM node in place without having to worry about returning anything:

class MyWidget(widgets.Widget):

def setUp(self, request, node, data):

newNode = request.d.createTextNode(str(data))

node.appendChild(newNode)

Widget also supports a very useful and convenient method called getPattern which allows you to locate nodes in the template node which have a pattern= attribute on them, regardless of where they are in the template, what style the node is, or how many children the node has:

class MyPatternWidget(widgets.Widget):

def setUp(self, request, node, data):

if data > 10:

newNode = self.getPattern("large")

else:

newNode = self.getPattern("small")

node.appendChild(newNode)

This widget could be used with the following template to abstractly allow the designer to style elements which are larger than 10:

<div model="listOfIntegers" view="List">

<div pattern="listItem" view="MyPatternWidget">

<span pattern="large" style="background-color: red" view="Text" />

<span pattern="small" style="background-color: blue" view="Text" />

</div>

</div>

Notice how the Widgets chain themselves to create the final page; the List widget makes copies of the pattern node which have view="MyPatternWidget" on them; the MyPatternWidget widget makes copies of the pattern="large" or pattern="small" nodes which have view="Text" directives on them; and the Text widget inserts the actual model data from the list into the innermost <span> element.

Widgets, along with the DOM api and the getPattern helper method, provide a powerful way for you to write view logic in Python without knowing or caring what type of HTML nodes are in your Template.

Generating View structure using the DOM is very useful for separating the Template from the actual logic which structures the View. However, if you need to do a large amount of HTML generation in Python, it becomes very cumbersome quickly. lmx is a lightweight wrapper around DOM nodes that allows you to quickly and easily build large HTML structures from Python:

from twisted.web.microdom import lmx

class LMXWidget(widgets.Widget):

def setUp(self, request, node, data):

l = lmx(node)

for color in data:

l.div(style=

"width: 2in; height: 1in; background-color: %s" % color)

When an lmx instance is wrapped around a DOM node, calling a method on the lmx instance creates a new DOM node inside a new lmx instance. The new DOM node will have the same tag name as the name of the method that was called, and an attribute for each keyword argument that was passed to the method. The returned value is the new DOM node wrapped in a new lmx instance. Text nodes can be added to an lmx instance by calling the special method text.

lmx can enable you to quickly generate a large amount of HTML programatically. For example, to build a calendar for the current month, create a Widget which uses lmx to add DOM nodes to the incoming template node. Here is a complete example which when placed in an rpy and visited through the web will render the current month's calendar:

import time

import calendar

calendar.setfirstweekday(calendar.SUNDAY)

from twisted.web.microdom import lmx

from twisted.web.woven import widgets

class Calendar(widgets.Widget):

def setUp(self, request, node, data):

node.tagName = "table"

curTime = time.localtime()

curMonth = calendar.monthcalendar(curTime[0], curTime[1])

today = curTime[2]

month = lmx(node)

headers = month.tr()

for dayName in ["Su", "M", "T", "W", "Th", "F" , "S"]:

headers.td(

_class="dayName", align="middle"

).text(dayName)

for curWeek in curMonth:

week = month.tr(_class="week")

for curDay in curWeek:

if curDay == 0:

week.td(_class="blankDay")

else:

if curDay == today:

className = "today"

else:

className = "day"

week.td(

_class=className, align="right"

).text(str(curDay))

from twisted.web.woven import page

resource = page.Page(template="""<html>

<head>

<style type="text/css">

.week { }

.day { border: 1px solid black; height: 2em; width: 2em; color: blue }

.today { border: 1px solid red; height: 2em; width: 2em; color: red }

.blankDay { height: 2em; width: 2em;}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<div view="calendar" />

</body>

</html>""")

resource.setSubviewFactory("calendar", Calendar)

Sometimes, you need to create some view-rendering code for a very specific

purpose. Since this code will most likely not be reusable across pages, it is

irritating to have to create a Widget just to house this code. Thus, Woven

allows you to place specially named wvupdate_ methods on your Page

subclass. Think of a wvupdate_ method as a setUp method that lives

on the Page class. When Woven encounters a view= directive that matches with a

wvupdate_ method name, it will create a generic Widget instance and

call the wvupdate_ method instead of setUp.

Note that the generic Widget instance is passed in as the third argument to a wvupdate_ method instead of a DOM node instance. Often this fact is not important, however, if you wish to access a Widget API such as getPattern, you must do so using the widget argument rather than self:

class MyPage(page.Page):

def wvupdate_foo(self, request, widget, data):

if data > 10:

newNode = widget.getPattern("large")

else:

newNode = widget.getPattern("small")

newNode.appendChild(request.d.createTextNode(str(data)))

widget.appendChild(newNode)

It is often possible to use wvupdate_ methods to quickly prototype some View code, and generalize this code later. By moving the wvupdate_ code into a Widget subclass, you make this code available to many different Pages.

Woven uses a View stack to keep track of which View objects are currently in

scope. You can use this fact to provide View objects which contain a lot of

view-manipulation logic, but are still cleanly implemented. When Woven

encounters a node with a view= directive, it locates the View (by

looking for a wvfactory_ method) and places it on the View stack.

While this node is being rendered, the new View is in scope, and is searched for wvfactory_ methods before other Views and the Page object. Thus you can create a View which is made up of other smaller parts:

from twisted.web.woven import view, page

class ShowHide(view.View):

template = """<span>

<div view="hider">

<div pattern="contents" view="contents">

Here are the contents!

</div>

</div>

</span>"""

def wvupdate_hider(self, request, widget, data):

## We want the widget to be cleared before rendering

widget.clearNode = 1

hidden = int(request.args.get("hide", [0])[0])

if hidden:

opener = request.d.createElement("a")

opener.setAttribute("href", "?hide=0")

opener.appendChild(request.d.createTextNode("Open"))

widget.appendChild(opener)

else:

closer = request.d.createElement("a")

closer.setAttribute("href", "?hide=1")

closer.appendChild(request.d.createTextNode("Close"))

widget.appendChild(closer)

widget.appendChild(widget.getPattern("contents"))

def wvupdate_contents(self, request, widget, data):

widget.clearNode = 1

widget.appendChild(request.d.createTextNode("Some contents here"))

resource = page.Page(template="""<html>

<body>

<span view="showHide" />

</body>

</html>""")

resource.setSubviewFactory("showHide", ShowHide)